The American Dream: Signed, Sealed and Delivered

This seems to be a good place in the course of this story to quickly share a little background on Jacques Mossler’s riches and his road to them.

Jacques was born the youngest of three children in Romania, in 1896, as Jacques Moscovici (his surname later “Americanized” to Mossler). Jacques’ impoverished family immigrated to the U.S. in 1901, seeing the writing on the wall of the difficult times ahead for Jewish citizens in Eastern Europe, including but hardly limited to a recently enacted ban on allowing Jewish children in public schools and the fact that there was no economic opportunity for Jewish families.

To reach the land of hope and promise, the family set sail across the Atlantic in 1900 (Jacques was four years of age at this time) on the S. S. Lake Ontario, an old, rusty ship far from ideal for transoceanic travel, with passengers literally stuffed in cargo hold below the deck. (The ship was retired and scrapped for its metal shortly after the Moscovici’s voyage). The family arrived in Nova Scotia and travelled by train to Montreal, Canada, where they parked for several weeks as they awaited required paperwork to continue on to the U. S.

Then, the family ventured (again, by train) to Buffalo, New York, where they integrated into a Romanian community. Jacques’ parents separated a few years after they arrived in the States and he, at age 12, moved with his mother and siblings to Chicago, where he later dropped out of school so he could work and help the family financially.

To make some money, Jacques sold newspapers and candy at the corner of LaSalle and Monroe streets in downtown Chicago. It was at this corner, in this setting, that he learned a whole new world … Capitalism!

Jacques was an industrious youngster, peddling papers and candy and whatever else would earn him a few bucks, but also he was very likely working in some manner with the “mob” or at the very least, with the blessing of the mob. We can gather this because during this period of time in Chicago, most money-making ventures were in some way or another mob-controlled. Later activities pretty much confirm he was working with the mob.

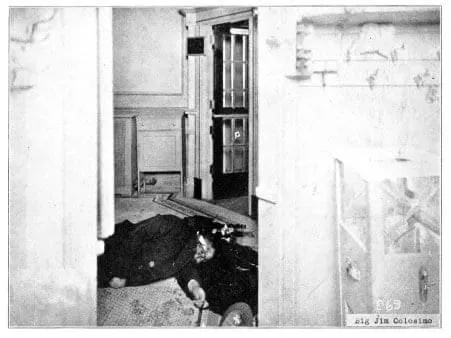

Jacques soon began hosting “numbers” games… think of the Lottery before there was a formal lottery. He learned the ways of gambling from the hosting end, and carried individuals’ “investments” to Vincenzo “Big Jim” Colosimo, a mob boss who built a criminal empire in Chicago based on gambling, racketeering and prostitution.

The mob empire was known as The Chicago Outfit, and after Colosimo was assassinated in 1920, it was controlled by Johnny Torrio and then later by the man who bears a name most of us are familiar with… Al Capone.

In learning about gambling from all sides, young Jacques learned that people would borrow money to gamble. Watching the business side of things taught the young teenager Jacques Mossler the art of hustling money and loaning money.

Jacques soon figured out how to make more money as a street financier than he ever made selling newspapers and candy. This sort of hustle became something that brought him great fulfillment, not to mention financial independence, and eventually, he made a career out of it.

At the age of 19, Jacques moved to New Orleans in 1915, and began employment as a loan manager for a local car dealer. Three years later, he incorporated a used car entity, Mossler Motor Exchange. He operated at 1515 Canal Street in the Central Business District initially and then sometime shortly after the turn of the decade to the Twenties, he opened shop at 739 St. Charles Avenue nearer the French Quarter.

He likely still worked with the Chicago mob through this business and not only did he (and the mob) capitalize on the high interest rates charged to individuals who borrowed money for cars, but he also capitalized on the repossession of the cars when the loans were unpaid. Mossler rented and/or sold vehicles that were repossessed, and effectively, he established one of the first businesses in the Southern United States that rented automobiles.

A review of The (New Orleans) Times Picayune newspapers shows he advertised automobiles which could be purchased through his Mossler Motor Exchange from 1917 through at least 1926. Advertisements boasted a “clean and quiet” indoor showroom and after hours opportunities including being open nights and Sundays.

For Jacques Mossler, the timing was perfect for loaning money to enable Americans to purchase their own vehicles. Mass production of vehicles was just a few years old and people were itching to participate in the automobile revolution by getting their own cars. They just needed help to come up with the approximately $1,000 to purchase a car. Mossler was ready, willing and able to loan them the money. Where the Ford Motor Company declined to finance cars, because the company’s founder and president, Henry Ford, wanted no part of having to repossess cars from families who fell on hard times, Mossler gladly stepped in to give out the money. “Repos” were part of the deal and as far as Mossler saw it, repossessions were just another way to make money when the loan installments quit coming for whatever reason.

A feature article in a 1922 edition of the daily newspaper, The Times Picayune, boasted of young Jacques’ business acument in the car world, touting him as an “oak of considerable sturdiness and dimension,” having grown from an acorn planted in NOLA just seven years earlier to a “seasoned hardihood!” He was described as the “owner, chief salesman, and director-in-chief” of Mossler Motor Exchange. Writer Edgar Boutwell noted that Mossler was attracted to New Orleans from Chicago by the climate and warm sunshine, and “the air of promise” in the charming Southern city. When he arrived in New Orleans, he first was selling signs for “a Chicago concern” and it happened that he needed a car, the article explained. He bought a Ford roadster, but soonafter a friend offered to sell him a Buick speedster for $70 and even though he hardly needed two cars, he figured it was too good of a deal to pass up, even though it was in disrepair. Mossler told the writer that he was able to fix it up a bit because he had once worked with his father in a bicycle repair shop which later became an automobile “hospital” (though when is hard to figure since he was a young boy when he moved to the States and soonafter separated from his father when he moved to Chicago). He ran a small ad in the newspaper and the next day got so many responses (and sold the car for a “handsome profit”) that he saw opportunity in selling cars.

“The decision was made, there would be a new automobile business in New Orleans,” and Mossler rented a place on Baronne Street before the new owner of the Buick had even picked up their new used vehicle. Mossler said he started with $7.72 in the bank, and right after opening day, but with the profit from the speedster, he was able to buy first one more used car, and then another, and another, making revolving loans and expediting turnover of the vehicles. Soon, he hired a mechanic to overhaul the cars.

“Today, he would buy the used car, the mechanic would work on it, and tomorrow it would be advertised.” Business grew so quickly that he began to purchase automobiles from larger, more distant cities… specifically New York and Chicago… and hauling them to New Orleans. He weathered the Depression and came out even stronger. Mossler attributed his successes to a simple ethic… “Work.” He relished the challenge.

“Perhaps if the path had been easier, I would still be selling signs or something else for somebody else,” he said.

Within a little over a decade of being in New Orleans, Jacques founded Mossler Acceptance Corporation, an independent lending company. He established offices in New Orleans, Dallas and Houston. Car dealers from throughout the Southern United States were soon sending loan applications through Mossler’s business.

In the 1950s, Mossler acquired the Allen Parker Auto Finance Company in Miami, expanding his installment loan empire to the Atlantic coast.

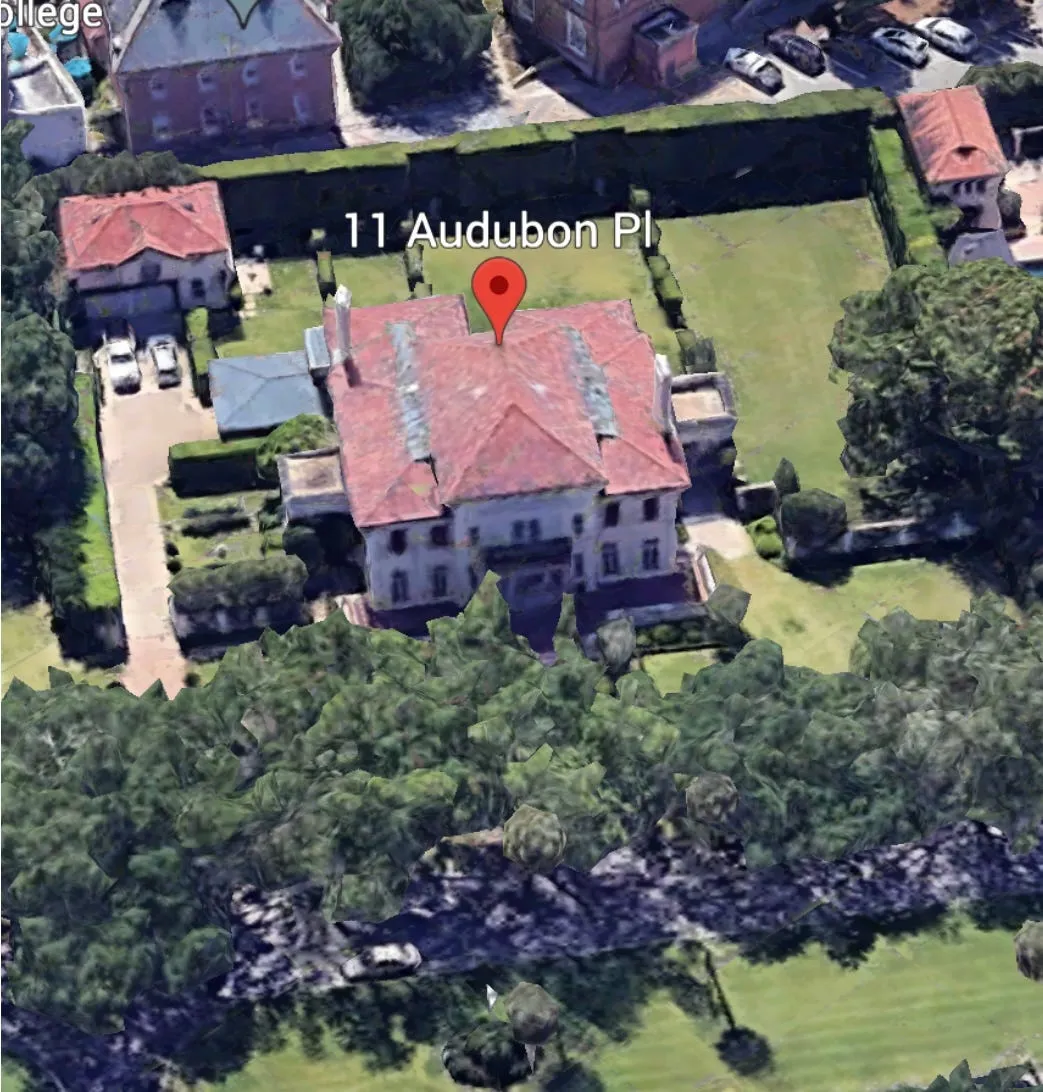

On the personal side of things, not long after moving to New Orleans, in 1917, Jacques married a 17-year-old local girl, Evelyn Mae Kizer, from the “West Bank” of New Orleans. In 1930, the couple had their first child, Jacqueline (named after Jacques), and by 1935, they had three more daughters, Bonnie, Marilyn and Evelyn. In 1944, the family moved into one of the Crescent City’s most exclusive neighborhoods, at 11 Audubon Place.